The first words in Homecoming, the new Netflix documentary that expands on Beyoncé’s landmark 2018 Coachella performance, come not from the singer, but from the author Toni Morrison. “If you surrender to the air, you can ride it,” the title card reads, a slightly modified quote from Morrison’s 1977 novel, Song of Solomon.

After about 15 minutes of performance footage capped by the Lemonade surprise single “Formation,” the documentary shifts to a glimpse into the process of pulling the Coachella performance together. The first thing that viewers hear after the final echoes of “Formation” is the voice of the late Nina Simone, played over recordings from some of Beyoncé’s Coachella rehearsals, which spanned eight months:*

I think what you’re trying to ask is why am I so insistent upon giving out to them that blackness, that black power, that black—pushing them to identify with black culture, I think that’s what you’re asking. I have no choice over it in the first place. To me we are the most beautiful creatures in the whole world—black people. My job is to somehow make them curious enough, persuade them by hook or crook, to get more aware of themselves and where they came from and what they are into and what is already there, just to bring it out. This is what compels me to compel them, and I will do it by whatever means necessary.

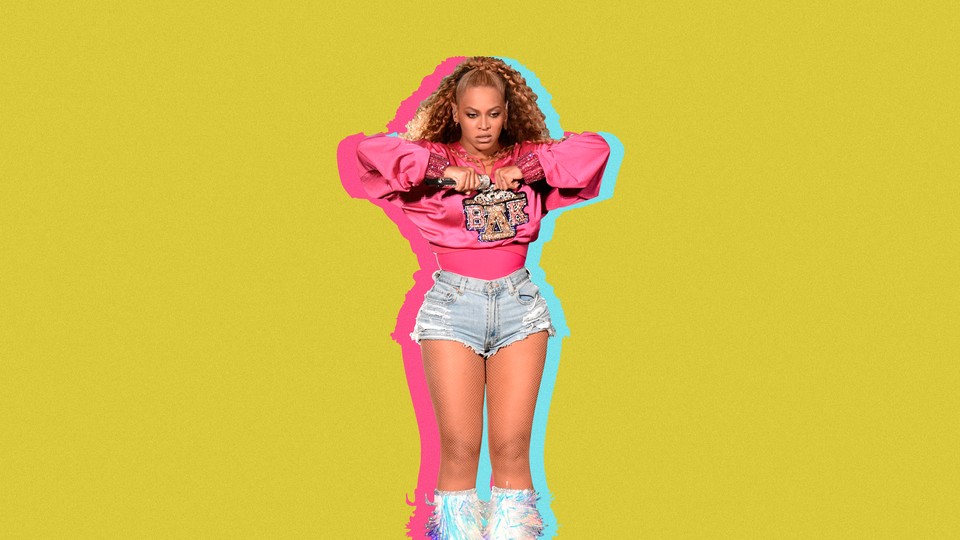

For Beyoncé, Homecoming presents another opportunity to continue the boundary-shifting, semiotic work of the Coachella performance, which itself was built on the black-feminist symbolism of Lemonade and the artistic foundation she’d established for years beforehand. The singer’s headlining 2018 set, which was nicknamed Beychella, was chock-full of references to black collegiate traditions—and also included a rendition of the black national anthem, “Lift Every Voice and Sing.” Her performance served a sly dual function: For black audiences, it was a masterly celebration of familiar traditions, including social dance; for white viewers, it was an introduction and an assertion of her deeply rooted prowess. “Instead of me pulling out my flower crown, it was more important that I brought our culture,” she says of the festival experience.

It’s fitting, then, that Homecoming is now an extension of this artistic double consciousness (and notably quotes W. E. B. Du Bois, who coined the term). Throughout the documentary, Beyoncé weaves in text and audio snippets from multiple black authors, historians, and public thinkers, most often culling from moments when they spoke directly to black audiences. The nearly two-and-a-half-hour production, which Beyoncé wrote, directed, and executive-produced, is as much a celebration of black-intellectual history as it is a concert film. (It’s also joined by a surprise live album of her Coachella set, which includes a bonus cover of the Frankie Beverly and Maze classic “Before I Let Go.”)

Early into Homecoming, Beyoncé explains the particular significance that historically black colleges and universities have held in her personal and artistic life. The Houston-born singer grew up near Prairie View A&M University and spent much of her early career rehearsing at Texas Southern University. She notes that, like Du Bois, her father is a graduate of Nashville’s Fisk University, and she always dreamed of attending an HBCU herself, but says, “My college was Destiny’s Child. My college was traveling around the world, and life was my teacher.” So when it came time for her to headline Coachella, she channeled the institutions’ distinct vibrancy: “I wanted a black orchestra. I wanted the steppers. I needed the vocalists. I wanted different characters; I didn’t want us all doing the same thing.” (She also established a scholarship program for HBCU students after last year’s performance.)Homecoming is, of course, a product—and Beyoncé is, fundamentally, an entertainer—but it’s still thrilling to see the world’s foremost musical talent giddily dedicate so much of her massive project’s screen time to citing a diverse array of black scholars. Not all of the thinkers the artist quotes throughout her documentary are graduates of an HBCU, but Homecoming still pulses with the kind of energy that black artists harness most often when working collaboratively with their own.

Their work buoys Beyoncé and her audiences alike, and Homecoming takes care to credit HBCUs when applicable: If Howard University’s Morrison nods to the beauty of artistic surrender, then of course Beyoncé, who cheekily called herself a “black Bill Gates in the making” on “Formation,” would also quote the late businessman Reginald Lewis, a graduate of Virginia State University.